Sonja Kips by Gustav Klimt (1898, Belvedere Vienna)

Sonja Knips was a society lady from an aristocratic family, but married an industrialist, making her a part of the new urban elite, or “Geldadel” of Vienna around the 1900s. [4] If we take a closer look at it, we see a woman on the edge of her seat, and the physical space around her has disappeared due to the dark colours used. Her gaze is directed at the viewer, which we might view as calm or still, which is strange tension with her posture, which seems uneasy and nervous. Focussing on the hand especially, we see a tense body of this “modern woman”, painted in a consciously “modern way” [5]. It was painted in 1898 by Gustav Klimt and exhibited in the Eighteenth Exhibition of the Vienna Secession in November 1903. Progressive critics considered these paintings to be modern because of the way they were psychologically charged, allowing the viewer to see the agitation and restlessness of the subject.

In 1897, an art movement was started in Austria. Known as the Vienna Secession or Vereinigung Bildender Künstler Österreichs, prominent painters, sculptors and architects came together to go against conservatism and Historicism in the arts, prevalent at that time in the Vienna Künstlerhaus and . Some of its prominent members were Otto Wagner, Joseph Hoffmann, Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt. This blog will focus on two famous paintings of the Modern Woman by Klimt and the way they fit into discourses on modernity, nervous illnesses and women in 1900 Vienna (which was, not by coincedence, also the home-town of Sigmund Freud). Did Klimt’s paintings merely express the sentiments and thoughts of the time or did his works also contribute to the discussions?

Lynda Nead, in her Myths of Sexuality: Representations of Women in Victorian Britain, outlines the way she examined the role of visual culture “in the definition of femininity and respectability in the mid-Victorian period”.[1] Her approach to achieving this goal will be the basis for mine, in analysing the visual material of Gustav Klimt and the discourses surrounding it.

A big part of Nead’s framework is based on the French philosopher Michel Foucault’s work The History of Sexuality. In this book, Foucault focuses on different discourses on sexuality, for example in medicine, psychiatry and criminal justice, and the power relations that are behind these discourses. According to Nead, no discourse can be looked at in isolation. [2] Therefore she looks at the interrelations between “official discourses” and tries to locate visual culture within these, to find out more about the role of these visuals. It would be an oversimplification to state that visuals or paintings in this case are simply a true reflection of the real world. It would also be an oversimplification to state they are a mirror of ideological interests of the time. According to Nead, visual culture is not a neutral vehicle that absorbs and transmits ideology, but rather a practice of representation and a practice of transforming and mediating the world at once. [3]

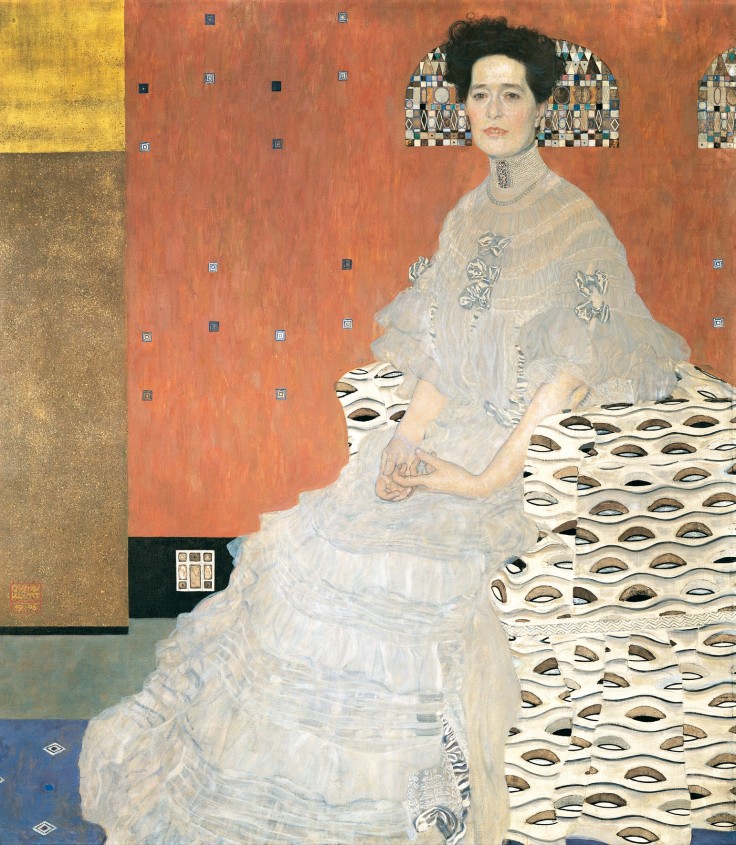

Fritza Riedler by Gustav Klimt (1906, Belvedere Vienna)

Let’s look at a second painting of Klimt, called “Fritza Riedler” which was painted in 1906 and exhibited in 1908. Even though his paintings go more into the style of decoration and ornamentation, we still see a high-society woman of German descent portrayed. If we look at the same elements as in the last painting, the gaze and the hands, we can see similarities. The gaze is again pointed at us, but at the same way it is not. The gaze seems distant and absent, as though she is not really there. Her hands, although not tense, again seem to show a sort of anxiousness, as though they “physically materialise the mental strains of the sitter’s nervousness and neurasthenic state” [6]

In 1885, the prominent Austrian psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing published his book Über Gesunde und Kranke Nerven. This book focuses on nervous ailments such as neurasthenia, hysteria and hypochondria, which he distinguishes from more serious and permanent mental illnesses. Neurasthenia was seen as a distinctly modern condition, as an answer to the vulnerability of the modern man in a society that was changing every day through industrialisation, urbanisation, technical innovation and changing social structures.[7] It was seen as a disease mostly for young people from higher classes, who “had committed to progress and modern achievements, but were losing their soul”.[8] Women, the upper-classes and so-called “brain-workers” were most susceptible to the disease. Thus, class and gender played big parts in the diagnosis of the disease.

For Kraft-Ebing, the cure to neurasthenia lay in a change of environment: new surroundings characterised by simplicity and planning. These were then provided by modernist architect Otto Wagner, who was also part of the discourse, in the form of the Steinhof psychiatrical hospital.

In his works, Klimt sought to define the image of the modern woman. As seen in the analysis, the concept of the “modern woman” is constructed through discourses of class, medicine and psychiatry. Whereas doctors and psychiatrists tried to find remedies for the modern disease called neurasthenia, Klimt celebrated the kind of femininity found in his portraits of neurasthenic society ladies. By creating a canvas in which the internal world of the sitter is brought to the surface, Klimt was seen to successfully dismantle the barrier between interior and exterior worlds, and thus breaking conventions with nineteenth-century naturalism. In this manner, we can say Klimt simply painted portraits that reflect the looks of these Viennese society women, whilst at the same time transmitting the ideology that to be a modern woman is to be nervous, to be a fragile beauty. In their turn, the highly popular and famous works of Gustav Klimt have also added to the discourse on the modern woman and especially the allure of nerves and neurasthenia.[9]

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

For more information on “The Lower Austrian Provincial Institution for the Care and Cure of the Mentally Ill and for Nervous Disorders ‘am Steinhof’” and the role of architecture within psychiatry see for example:

- Topp, L. (2005). Otto Wagner and the Steinhof Psychiatric Hospital: architecture as misunderstanding. The Art Bulletin, 87(1), 130-156.

- Topp, L. E. (2004). Architecture and Truth in Fin-de-siècle Vienna (Vol. 32). Cambridge University Press.

[1] Nead, L. Myths of Sexuality. Representations of Women in Victorian Britain. (Oxford: Basis Blackwel, 1988), pp.10

[2] Ibid, pp. 4

[3] Ibid, pp. 8

[4] Topp, L., Blackshaw, G., and Wellcome Collection. Madness and Modernity: Mental Illness and the Visual Arts in Vienna 1900. (Lund Humphries, 2009) pp. 127

[5] Ibid, pp. 127

[6] Ibid, pp. 133

[7] Johannisson, K. Het Duistere Continent: (Uitgeverij van Gennep, 1995), pp. 135

[8] Ibid, pp. 135

[9] Topp, L., Blackshaw, G., and Wellcome Collection. Madness and Modernity: Mental Illness and the Visual Arts in Vienna 1900. (Lund Humphries, 2009) pp. 133

Leave a comment